The Pitfalls of Effective Altruism: A Cautionary Tale

The Philosopher-Founders and Their Flawed Approach

Effective altruism (EA) is a philosophy that has gained traction in recent years, with its proponents claiming to have found the most effective ways to help the world’s poor. However, upon closer examination, the approach taken by the philosopher-founders of EA is riddled with issues. Like the author in 1998, these individuals had no background in aid, yet they confidently promoted charities based on simplistic calculations of “lives saved” per dollar spent. This narrow focus on quantifiable metrics fails to account for the complex realities of poverty and the potential unintended consequences of interventions.

The Importance of Responsibility and Accountability

When deciding to intervene in the lives of the poor, it is crucial to do so responsibly and with accountability. The most important point to make to EAs is that extreme poverty is not about the interveners; it’s about the people facing daily challenges that most of us can hardly imagine. Shifting power to those affected and being accountable for our actions should be the primary concern of anyone seeking to make a positive impact.

The Rise of the Pitchman and the Billionaires

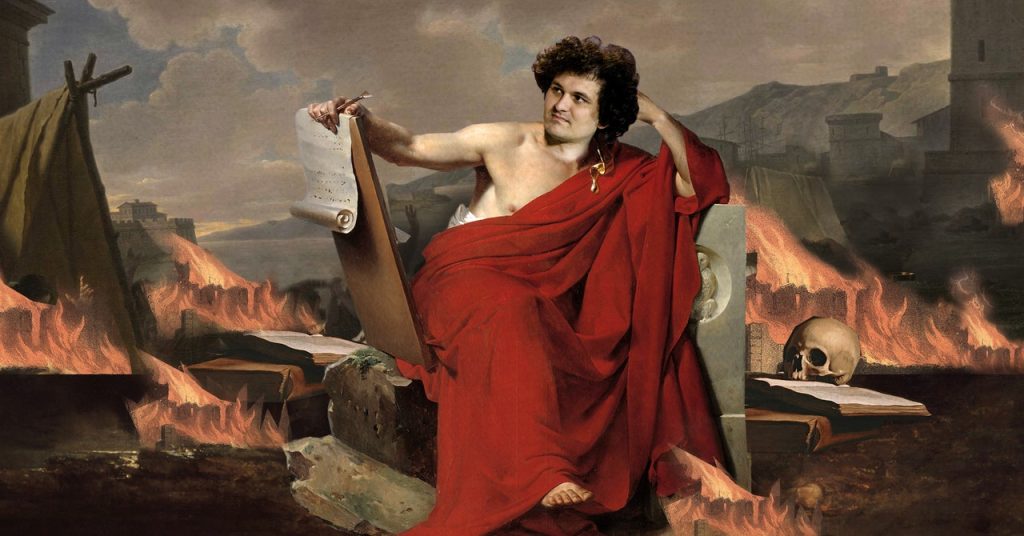

The emergence of Will MacAskill, another young Oxford EA with a PhD in philosophy, marked a turning point for the movement. MacAskill’s shameless promotion of EA, exemplified by his pitch book “Doing Good Better,” caught the attention of billionaires like Sam Bankman-Fried. MacAskill’s concept of “earning to give” encouraged the wealthy to pursue financial gain in order to donate more to EA causes.

The Dangers of Oversimplification and Hype

MacAskill’s claims about the impact of aid on sub-Saharan life expectancies are a prime example of the oversimplification and hype that plagues the EA movement. His dismissal of microcredit and promotion of deworming pills as the latest “solution” to poverty demonstrates a lack of understanding of the complexities involved. The subsequent downgrading of deworming charities by GiveWell, an organization that had previously given them top ratings, highlights the risks of relying on simplistic metrics and failing to consider potential side effects.

The Importance of Consent and Local Engagement

The story of the Chinese trillionaires and the sick children, based on real events in Tanzania, underscores the importance of obtaining consent from those affected by aid interventions and engaging with local communities. The angry response of parents who discovered their children had been given deworming pills without their knowledge or consent serves as a stark reminder of the potential for unintended consequences when aid is imposed from the outside.

The Failure of Effective Altruism’s Philosophy

Perhaps most damning is MacAskill’s failure to provide a clear definition of “altruism,” the very foundation of the philosophy he promotes. As a philosopher, one would expect him to be obsessive about defining the terms he uses, yet his simplistic statement that “altruism simply means improving the lives of others” falls far short of the rigorous analysis required for a coherent philosophical framework.

I want to be clear on what [“altruism”] means. As I use the term, altruism simply means improving the lives of others.

In conclusion, while the intentions of effective altruists may be admirable, the approach taken by the movement’s leaders is deeply flawed. By oversimplifying complex issues, relying on questionable metrics, and failing to engage meaningfully with those they claim to help, effective altruists risk causing more harm than good. A more responsible and accountable approach, grounded in a genuine understanding of the realities of poverty and a commitment to empowering those affected, is essential if we are to make a lasting, positive impact on the world’s most vulnerable populations.

The Flawed Philosophy of Effective Altruism and Sam Bankman-Fried

Redefining Altruism

The concept of altruism, as defined by William MacAskill, is fundamentally flawed. True altruism involves acting on a selfless concern for the well-being of others, considering both the why and the how. However, MacAskill’s definition allows for a totally selfish person to be considered an “altruist” if they improve others’ lives unintentionally. Even a character like Sweeney Todd, who kills Londoners to make meat pies, could be considered an altruist under this distorted definition.

The Credit Conundrum

MacAskill’s philosophy of giving credit is equally problematic. He argues that the measure of one’s achievement is the difference made in the world, comparing donating to a charity that provides insecticide-treated bed nets to saving a child from a burning building. However, this view fails to acknowledge the agency and choices of others involved, such as the mother who trusts the aid workers and uses the bed net to protect her child. It would be more accurate to say that the donation offers the mother the opportunity to save her own child’s life.

The Double-Edged Sword of Responsibility

If we accept MacAskill’s logic that each person is responsible for everything that wouldn’t have happened without their actions, then it follows that they are also responsible for the negative consequences. Given that MacAskill persuaded Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) to pursue a career in finance instead of animal welfare, he should, by his own theory, be held accountable for SBF’s actions in the financial world.

The Allure of Expected Value Thinking

Effective Altruism’s (EA) philosophy resonates with tech billionaires because it relies on the concept of “expected value” thinking, a tool commonly used by venture capitalists. This approach involves calculating the expected value of various options to maximize returns. EA applies this method to morality, encouraging people to make choices that yield the highest expected value for the universe. Organizations like GiveWell and 80,000 Hours promote this mindset, guiding individuals to earn high incomes in finance to donate more money to EA causes.

The Dangers of Extreme Rationality

SBF embodies the extreme application of expected value thinking, attempting to calculate the expected value of every choice he makes. This “rational” approach, free from emotional connections to others, is encouraged by EA. However, it can lead to dangerous decisions, such as SBF’s willingness to play a godlike game where there’s a 51% chance of creating another Earth but a 49% chance of destroying all human life. This mindset treats people as resources to be optimized for maximum value, blurring the lines between personal gain and the greater good.

The Blurred Lines of Altruism and Selfishness

In the end, it remains unclear whether SBF was truly aiming for maximum value for the universe or maximum value for himself. The convergence of these two aims in his mind may have led to his downfall, as he prioritized short-term profits over essential aspects of running a company, such as hiring auditors and a chief financial officer. The flawed philosophy of EA, combined with SBF’s extreme application of expected value thinking, ultimately resulted in terrible choices and alleged criminal behavior.

The Downfall of Sam Bankman-Fried: A Cautionary Tale for Effective Altruists

The Irrational Calculations of SBF

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF), the disgraced founder of FTX, made a series of irrational decisions that ultimately led to his downfall. Despite his claims of using expected value thinking to justify his actions, his calculations were severely flawed. When his frauds were exposed, he attempted to manipulate the narrative by leaking his diaries to the press. However, the judge saw through his deception and threw him in jail. During the trial, SBF insisted on testifying, but his performance on the stand was abysmal. As Daniel Kahneman aptly stated:

We think, each of us, that weâre much more rational than we are.

SBF’s self-deceptions finally collided with reality when the jury found him guilty of seven counts of fraud and conspiracy. He now faces a 25-year prison sentence as a consequence of his irrational actions.

Effective Altruism and Self-Deceit

When SBF’s frauds were revealed, Effective Altruism (EA) philosophers tried to distance themselves from him. However, young EAs should carefully consider how much their leaders’ reasoning shared the flaws of SBF’s. The philosophers, too, blurred the lines between what was good for others and what was good for themselves. They indulged in extravagant purchases, such as buying a medieval English manor and a Czech castle for their team. They flew private, ate $500-a-head dinners, and launched a lavish promotion campaign for MacAskill’s second book. These personal benefits were easily justified by the philosophers who believed they were bringing extraordinary goodness to the world. However, philosophy does not provide immunity against self-deceit.

The Expansion and Paradox of EA

While SBF’s money was still flowing, EA significantly expanded its recruitment of college students. GiveWell’s Karnofsky moved to an EA philanthropy that distributes hundreds of millions of dollars annually and established institutes with grand names like Global Priorities and The Future of Humanity. EA began to synergize with related subcultures, such as transhumanists and rationalists. EAs even filled the board of a Big Tech company they later nearly crashed. EA was suddenly everywhere, becoming a phenomenon.

However, this was also a paradoxical time for EA’s leadership. While their following grew larger, their thinking appeared increasingly questionable.

The Illusion of GiveWell’s Effectiveness

During the prosperous times, GiveWell’s pitch pages enticed donors by promoting its “in-depth evaluations” of “highly effective charities” that do “an incredible amount of good.” The pitch included specific figures, such as the cost to “save a life” (now up to $3,500) and the total lives GiveWell has “saved” (now up to 160,000). However, upon closer examination, these claims proved to be dubious.

The Illusion of Precision: Examining the Evidence Behind GiveWell’s Top Charity Recommendations

Deworming Charity: A Closer Look

For nearly a decade, GiveWell, a nonprofit organization that conducts in-depth research to find and recommend highly effective charities, had consistently ranked a deworming charity among its top recommendations. However, in 2022, this changed. Upon closer examination of the sub-subpages on GiveWell’s website, it became apparent that the precise figures used to support the charity’s effectiveness were based on weak evidence and numerous caveats.

GiveWell claimed that their “strongest piece of evidence” for the deworming charity’s impact was a single interview with a low-level government official in just one of the five countries where the charity operated. This revelation raises questions about the robustness of the evidence used to justify the charity’s top ranking.

The Fine Print: Hedging and Uncertainty

While GiveWell’s main pages project absolute confidence in their exact numbers, the nested links tell a different story. The calculations are littered with phrases like “very rough guess,” “very limited data,” “we don’t feel confident,” “we are highly uncertain,” and “subjective and uncertain inputs.” GiveWell even admits that their cost-effectiveness numbers are “extremely rough” and “should not be taken literally.”

William MacAskill’s Second Book: Fur Coat and No Knickers

William MacAskill, a prominent figure in the effective altruism movement, released his second book, “What We Owe the Future,” which has been described as even more shameless than his first. While his first book advised readers on where to donate their money, the second book goes a step further, offering guidance on how to run most aspects of one’s life.

Up front,

4 Comments

So the gift of giving hit a snag, huh? Figures nothing’s bulletproof, not even altruism.

Effective Altruism fizzling out? Maybe it’s time to rethink our approach to doing good in the world.

Oh, so now saving the world isn’t cool enough? Funny how trends change, isn’t it!

Could the downfall of Effective Altruism really just be a sign that it’s evolving, or is it truly a crisis