DOJ and FTC Challenge Hotels’ Claims in Algorithmic Price-Fixing Lawsuit

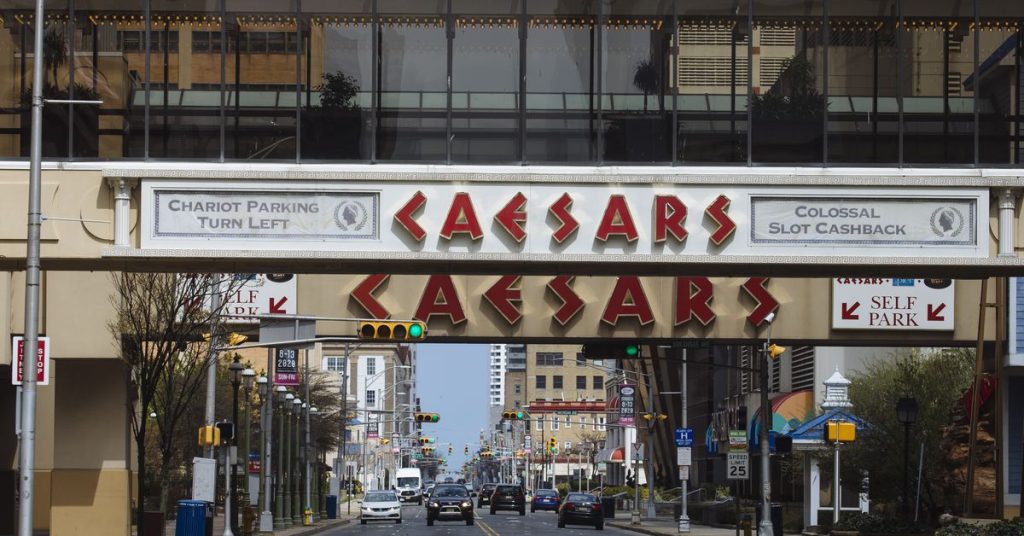

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have jointly submitted a statement of interest in a class action lawsuit, Cornish-Adebiyi v. Caesars Entertainment, brought by New Jersey residents against several Atlantic City hotels. The plaintiffs allege that these hotels engaged in an illegal price-fixing conspiracy through the use of a common pricing algorithm platform called Rainmaker.

Plaintiffs Seek to Prove Violation of Sherman Act

The plaintiffs aim to demonstrate that the hotels violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits “conspiracy in restraint of trade” and is used to prosecute illegal price-fixing. They argue that the hotels knowingly used the Rainmaker platform, aware that their competitors were also using it, and chose it for that reason.

Agencies Emphasize Importance of Judicial Treatment

The DOJ and FTC stress the significance of how this issue is handled, stating,

Judicial treatment of the use of algorithms in price fixing has tremendous practical importance.

The agencies have filed similar statements in other algorithmic price-fixing cases, such as a lawsuit against RealPage, a rental property management software company accused of contributing to higher rental prices through its access to and use of nonpublic pricing data from landlords.

Challenging Hotels’ Claims for Dismissal

The DOJ and FTC are challenging two claims made by the hotels to dismiss the lawsuit. First, the hotels argue that the plaintiffs needed to allege direct communication between the hotels to prove a Sherman Act violation. Second, they claim that the suit should be dismissed because the pricing algorithm only produced recommendations, not binding price requirements.

Agencies Refute Hotels’ Arguments

The enforcers argue that these claims are incorrect. They state that there is no legal requirement for plaintiffs to allege specific communications directly among competitors to allege an agreement subject to Section 1. They also assert that it is irrelevant that the algorithm’s recommendations were non-binding, as precedent for Section 1 of the Sherman Act shows that fixing list or sticker prices is illegal, even if the ultimate prices charged are different.

The agencies emphasize that the violation lies in the agreement itself, not in how often it is followed. They warn that accepting the hotels’ perspective could allow a price-fixing cartel to avoid punishment by including competitors who tend to deviate from the fixed prices or by agreeing to allow some deviation.

As the lawsuit progresses, the court’s decision on these issues will have significant implications for the treatment of algorithmic price-fixing in antitrust cases.

1 Comment

So, algorithms are the new mobsters of the market, eh? Interesting!